Picture a uniform, unbroken expanse of sun bright cloud bed; the classic white sky day

Picture a uniform, unbroken expanse of sun bright cloud bed; the classic white sky day. Just such an afternoon was in bloom in southeastern Pennsylvania, and being a summer weekday, I had a forested run, from one narrow bend to the other, to myself. I heard no thunder, felt no rain, yet a steady shower of rise forms started to dot the water. The flow was too warm to hold wild trout, and the Pennsylvania Fish & Boat Commission never stocked the creek. What, then, was rising?

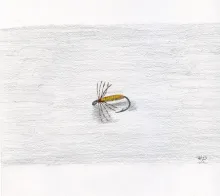

I attached tippet to Light Cahill and sent it upstream toward the bustling surface. My sidearm cast landed the dry fly in a dainty way that resembled a windblown milkweed seed coming to rest on the water. The visual poetry of the scene ended there, replaced by the action drama of an aggressive rise. The taker sucked under the pattern and made a fishhook U-turn upstream. Now I was grappling with an obstinate opponent. The fish did not jump, but rather worked with the current, using its body to plane against the water and make tight, circular runs. I assumed I had hooked into a bass until a flash of deep orange appeared just below the surface. Like a battlefield flag, the colors communicated the identity of my adversary: a (large) redbreast sunfish.

Lepomis auritus, the redbreast sunfish, does not receive the front-page press of its cousins the bluegill, the crappie, and the black bass. This species deserves increased specific attention, though, especially from fly anglers who prefer to fish flowing water, because the redbreast is the stream sunfish.

The ubiquitous bluegill and other “sunnies” are part of a large family of fish, Centrarchida, crowned by the largemouth and smallmouth bass. Bluegills, pumpkinseeds, and crappies are frequently lumped along with the largemouth and its favorite stillwater environments such as lakes, farm ponds, and wetland marshes, and rightly so. Warm, weedy waters provide the kind of cover where these stalking hunters can hide and ambush prey.

Redbreasts, however, side with the smallmouth. This rising sunfish thrives in the cooler, more oxygenated, flowing water environment of freestone rivers and streams and can be found throughout the mid-Atlantic region of the U.S. from the Carolinas north to southern New England. Tidal rivers and their many tributaries are the best places to seek out the biggest redbreasts, which can reach a length of ten inches and weights of up to two pounds.

The one stretched out in your hand can be distinguished from its kin by the long black ear flaps, forest green flanks, which are sometimes faintly barred, and the rich, flaming orange bellies that give this panfish its popular name. Redbreasts also have larger, wider jaws like the black bass rather than the tiny, puckered mouth of the bluegill. This bigger set of jaws would indicate redbreasts prefer a bigger bite, and they do.

Live Bait, Imitated, Where It Lives

Earthworms, crayfish, tadpoles, and minnows: all are effective live baits for redbreast sunfish. Large terrestrial insects, crickets and grasshoppers, are also excellent, especially during the summer months. Baits suited to a size 6 or 8 snelled hook would make an offering big enough to interest the redbreast’s appetite.

“Bait” can be a dodgy term when used in fly fisher campfire circles, so “Imitation” shall be used here from now on, and for more than flattery. Two examples of effective imitation from authoritative tiers include Dave Whitlock’s “NearNuff” creations and Harry W. Murray’s “Strymph” series. Both anglers have spent decades devoted to the smallmouth bass, its stream environment, and its stream kin, including the redbreast sunfish. Their patterns target the entire range of the water column, not just the top, and these variations imitate the larger forage base found in the depths: minnows, sculpins, crayfish, and hellgrammites.

The most effective stream sunfish rig allows an imitation to follow a smooth, subsurface drift with the current. Strike indicators are optional, and actually unnecessary, as it is important to keep the pattern rolling near the bottom like a natural cascading downstream. Small streams tend to flow rather quietly, so any strike from a sunfish will be readily apparent to the attentive angler.

Springtime’s high water conditions may require weighted patterns or else one or more non-toxic split shot placed a foot or so above the hook to get the fly down to the sunfish, which frequently hold in small schools at mid-depth. A cast across and downstream will allow the flow to carry the rig along the current seams and into eddies and pools where the redbreasts with be holding, and waiting, for dinner.

A redbreast will most often hit a subsurface fly near the end of a drift, or during the first one or two pulls of a retrieve. A sequence of staccato, darting pulls followed by a pause can tease this fish into making vicious strikes. The resulting rod-bending battle can be as exciting as a bass, and when larger redbreasts work with the current, the fight can best be described as reeling in a swimming saucer, sideways.

Redbreasts do not hold in and around partially exposed streamside structure the way bluegills, crappies, and largemouth bass tend to do in lakes and ponds. Structure that is completely submerged is more to their taste. You can see this preference on display, especially during the months of May and June, when the males gather to guard over their spawning beds in shallow water. This sunfish seeks calm rather than cover, so it is best to seek out sheltered areas of the river or stream adjacent to a current that provides a steady incoming flow of food.

A Symphony in Orange

The sunk fly is best when searching for schooling redbreasts, and the pattern that has best served me is the Partridge and Orange. How I came to discover this fact is an interesting story in itself.

The first fly fishing book I ever read from cover to cover was The Soft-Hackled Fly by Sylvester Nemes. My personal copy, a first paperback edition, came to me in an interesting way. A coworker who had a side business selling used books on eBay brought the title to my desk one day not long after I had returned to fly fishing, the story I told in my memoir, Philadelphia on the Fly: Tales of an Urban Angler. The charming storytelling and excellent photographs in his book inspired my own writing project and later helped me to relearn the fly-tying techniques I had picked up as a lad from my stepfather.

That initiation to tying flies sticks in the memory as a wintertime when we covered our circular dining room table with clear little bags of exotic, earth-toned biologicals and an assortment of black and silver metal tools. My stepfather, with my fly fishing mother’s approval, had caught the fly-tying bug, and he simultaneously taught me over the course of that snowy season the techniques needed to tie a simple gray nymph pattern, which I used later that year to catch... sunfish.

Twenty-five years later I acquired a heavy rectangular coffee table, etched with witty graffiti, which I had salvaged from some art school students moving off my block. Set up in a well-lit corner of my urban angler’s garret, stacked high with materials and a portable tool kit, I continued the table’s artistic legacy by using it to support my creation of sculpture made from thread, floss, feather, and fur. With Nemes’ book propped open by my side, I learned to tie once again, following each of his close-up photos in the proper order. Surprise! Success! The first pattern I remastered was the Partridge and Orange.

That spring I had a full fly wallet, and I found the pattern, especially its distinctive color, to be a killer sunfish fly. The photographer and self-described “bug nerd” Thomas Ames Jr. has written eloquent essays about this soft-hackle as well, and he believes it most resembles the Great Brown Autumn Sedge, Pyncopsyche guttifer; a caddis that, he observes, “is distinctly orange.” I agree with him, and it is no accident that redbreast sunfish populate coolwater streams where caddis predominate. So, to summarize: the Partridge and Orange imitates an orange sedge that lures the redbreast whose belly is actually a fiery... orange.

This fly fishing experience is a symphony in orange!

Dry-Fly Fishing 101

Redbreasts, being stream sunfish, are sensitive to hatches of insects. When caddis and mayflies begin to emerge, redbreasts will rush to engorge on both emergers and spent spinners.

Soft-hackled wets and general nymph patterns like the American Pheasant Tail or Prince will often be sufficient along a sunfish stream, but when hatches do occur, redbreasts will become as selective as trout, at least in regards to where they feed. Redbreasts divide the water column into living room and kitchen room levels. At hatch time, the kitchen is on the surface. Sure, there may be a few stray five- or six-inchers lingering below that will fall to a weighted nymph at any time, but when a hatch is on, the swimming Frisbees will be feeding up top. Being a big redbreast man, I prefer to go after those on the top tier.

Simple attractor patterns like the Adams, Elk Hair Caddis, and Light Cahill will match most of the hatches tempting redbreasts to the surface. One point to keep in mind is that caddis predominate in the coolwater transition stream environments redbreasts most prefer. CDC emergers and bead head caddis imitations will work when general patterns fail. A well-supplied fly box for redbreast sunfish will hold all of the above-mentioned patterns in sizes 8 through 16.

My personal pattern is a variation on the aforementioned Partridge & Orange, one that bridges the gap between a classic soft-hackle and a pure dry fly. Both categories of patterns can be challenging for the novice, as I myself learned, and this can sometimes lead to improper language on the part of the first-time tier. Partridge feathers are very fine, and wrapping the delicate hackle to create the sparse, flowing legs can frustrate the fingers. Elaborate dry flies with a multitude of exhausting ziggurat steps can lead to trapped hackles and other debacles. A simpler alternative is a hybrid variation I have coined the Easy & Orange, which fuses the E-Z Nymph of the late A. J. Campbell with the traditional soft-hackled color and shape popularized by Sylvester Nemes.

The pattern’s fundamental ingredient, taken from the E-Z- Nymph, uses a more manageable, and one of the most readily available, tying materials: pheasant tail. A decent tail can be had from a friendly bird hunter or local fly shop for just a few dollars and will provide fishing ammunition for dozens of flies. The other essentials to the recipe are black tying thread and orange floss.

To begin, tie in the floss and wrap it forward to create a smooth body that is slightly thicker in the middle of the hook shank. Tie off the floss and next add the pheasant tail fibers, wrapping these once or twice in front of the body. Tie off and then, folding the fibers back so that these are evenly distributed around the hook, tie down, completing the pattern with a few half hitches or whip finish.

The silhouette of the resulting pattern resembles the soft hackle, but the stiffer pheasant tail floats higher in the surface film. The fly can be fished upstream in wrinkled water, or with a traditional wet fly swing, one that will be interrupted frequently by insistent redbreasts if there are any swimming about.

I have presented this pattern on several Mid-Atlantic streams over three angling seasons and have concluded the Easy and Orange matches this sunfish’s specific selectivity. A size 14 pattern, on average, brought eight redbreasts and two secondary species, usually smallmouth or rock bass, to hand out of every ten fish caught. My control pattern, a size 14 Adams, fished along the same streams in similar fashion at the same time of year and under the same weather conditions produced, by comparison, a much more mixed catch: an average of five redbreasts, three smallmouth, and two tertiary species -- rock bass, green sunfish, or channel catfish -- out of every ten fish caught.

This is as scientific as I will allow myself to be where angling is concerned. I’ll take the unquantifiable beauty of stream scenery over the unending debate over catch statistics anytime. That stated, the evidence deduced from my research remains: the redbreast is a stream sunfish that, like the trout, will rise to the fly, especially the Easy and Orange. This meets my personal standard of a great fly rod game fish. And one of the most effective and rewarding ways to learn, or to teach, fly fishing is to hone one’s skill along a creek inhabited by redbreast sunfish. This is Dry-Fly Fishing 101. The skills, appreciation, and fun these brightly colored stream sunnies provide can set a new fly fishing life in stone.

The Stream Sunfish Kit

Basic Rig

3- to 5-weight fly rod and reel outfitted with floating line.

Fly Box

1) Adams Parachute, size 12, 14

2) Hare’s Ear Nymph, size 12, 14

3) Light Cahill, size 12, 14, 16

4) Murray’s Strymph, size 10, 12

5) Partridge and Orange, size 12, 14, 16

Other Necessities

Insect repellent, non-toxic split shot, polarized sunglasses, small landing net, wading staff

- Log in to post comments